Tesdorf Designs

Welcome to Architectural Information

WESTERN ARCHITECTURE 1

A HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE

PREHISTORIC TO ROMANESQUE PERIOD

Gobekli Tepe Ruins in Turkey, from about 9,000 and 7,000 B.C,

NEOLITHIC ERA

Neolithic Architecture

Architectural advances are an important part of the Neolithic period (10,000-2000 BC), during which some of the major innovations of human history occurred. The domestication of plants and animals, for example, led to both new economics and a new relationship between people and the world, an increase in community size and permanence, a massive development of material culture, and new social and ritual solutions to enable people to live together in these communities.

New styles of individual structures and their combination into settlements provided the buildings required for the new lifestyle and economy and were also an essential element of change. Although many dwellings belonging to all prehistoric periods and also some clay models of dwellings have been uncovered enabling the creation of faithful reconstructions, they seldom included elements that may relate them to art. Some exceptions are provided by wall decorations and by finds that equally apply to Neolithic and Chalcolithic rites and art.

In South and Southwest Asia, Neolithic cultures appear soon after 10,000 BC, initially in the Levant (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and Pre-Pottery Neolithic B) and from there spread eastwards and westwards. There are early Neolithic cultures in Southeast Anatolia, Syria, and Iraq by 8000 BC, and food-producing societies first appear in southeast Europe by 7000 BC, and Central Europe by c. 5500 BC (of which the earliest cultural complexes include the Starčevo-Koros (Cris), Linearbandkeramic, and Vinča).

Neolithic settlements and towns include:

Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, ca. 9,000 B.C.

Jericho in the Levant, Neolithic from around 8,350 B.C., arising from the earlier Epipaleolithic Natufian culture

Nevali Cori in Turkey, ca. 8,000 B.C.

Çatalhöyük in Turkey, 7,500 B.C.

Mehrgarh in Pakistan, 7,000 BC

Knap of Howar and Skara Brae, the Orkney Islands, Scotland, from 3,500 B.C.

3,000 settlements of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, some with populations up to 15,000 residents, flourished in present-day Romania, Moldova, and Ukraine from 5,400 to 2,800 B.C..

Göbekli Tepe (Turkey), c.9500-8000 B.C

Wooden houses (Hemudu, China), 5000-4500 B.c.

Skara Brae (Scotland), 3200-2200 B.C.

House Ruins at Skara Brae, Scotland 3200-2200 B.C.

MESOPOTAMIA

Architecture of Mesopotamia

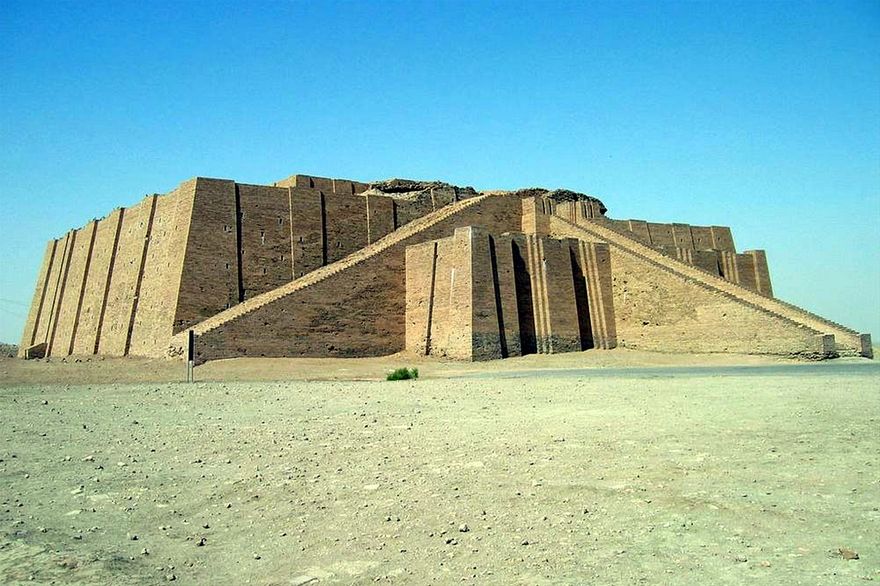

Mesopotamia is most noted for its construction of mud-brick buildings and the construction of ziggurats, occupying a prominent place in each city and consisting of an artificial mound, often rising in huge steps, surmounted by a temple. The mound was no doubt to elevate the temple to a commanding position in what was otherwise a flat river valley. The great city of Uruk had a number of religious precincts, containing many temples larger and more ambitious than any buildings previously known.

The word ziggurat is an anglicized form of the Akkadian word ziqqurratum, the name given to the solid stepped towers of mud brick. It derives from the verb zaqaru, ("to be high"). The buildings are described as being like mountains linking Earth and heaven. The Ziggurat of Ur, excavated by Leonard Woolley, is 64 by 46 meters at the base and originally some 12 meters in height with three stories. It was built under Ur-Nammu (circa 2100 B.C.) and rebuilt under Nabonidus (555–539 B.C.) when it was increased in height to probably seven stories.

Assyrian palaces had a large public court with a suite of apartments on the east side and a series of large banqueting halls on the south side. This was to become the traditional plan of Assyrian palaces, built and adorned for the glorification of the king. Massive amounts of ivory furniture pieces were found in some palaces.

Dur-Sharrukin ("Fortress of Sargon"; Arabic: دور شروكين, Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mosul. The great city was entirely built in the decade preceding 706 BC. After the unexpected death of Sargon in battle, the capital was shifted 20 km south to Nineveh.

Nineveh was the capital of the powerful ancient Assyrian empire, located in modern-day northern Iraq. Sennacherib was the king of Assyria from 704–681 BC and was famous for his building projects. The rooms and courtyards of his Neo-Assyrian Southwest Palace at Nineveh were decorated with a series of detailed carved stone panels. Many of these stone panels are on display in the British Museum. The panels depict a variety of scenes, including the transport of huge sculptures of human-headed winged bulls (lamassu) that weigh up to 30 tons and were intended for the main entrances to the palace.

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were famous as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. However, the gardens were, according to Stephanie Dalley, an Oxford University Assyriologist, located some 340 miles north of ancient Babylon in Nineveh, on the Tigris River by Mosul in modern Iraq.

The Ziggurat at Ur, 21st century BC, Tell el-Muqayyar (Dhi Qar Province, Iraq)

Winged human-headed bull (lamassu or shedu), reign of Sargon II (721-705 B.C.) Khorsabad, ancient Dur Sharrukin, Assyria, Iraq, in the Louvre

Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate from Babylon, c. 605-539 B.C. faced with glazed bricks now in the Pergamon Museum (Berlin, Germany)

ANCIENT EGYPT

Ancient Egyptian architecture

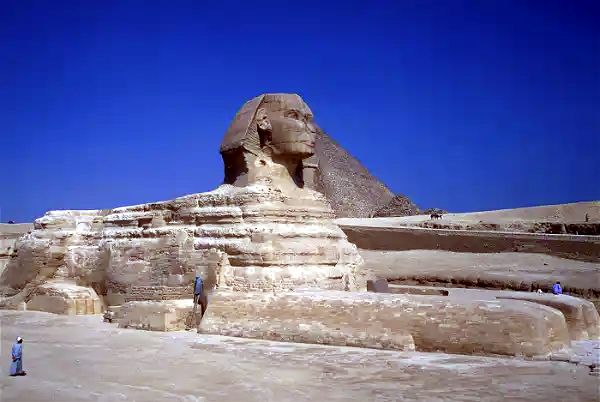

Modern imaginings of ancient Egypt are heavily influenced by the surviving traces of monumental architecture. Many formal styles and motifs were established at the dawn of the pharaonic state, around 3100 B.C. The most iconic Ancient Egyptian buildings are the pyramids, built during the Old and Middle Kingdoms (c.2600–1800 B.C.) as tombs for the pharaoh. However, there are also impressive temples, like the Karnak Temple Complex.

The Ancient Egyptians believed strongly in the afterlife. They also believed that in order for their soul (known as ka) to live eternally in their afterlife, their bodies would have to remain intact for eternity. So, they had to create a way to protect the deceased from damage and grave robbers. This way, the mastaba was born. These were adobe structures with flat roofs, which had underground rooms for the coffin, about 30 m down. Imhotep, an ancient Egyptian priest, and architect had to design a tomb for the Pharaoh Djoser. For this, he placed five mastabas, one above the next, this way creating the first Egyptian pyramid, the Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara (c.2667–2648 B.C.), which is a step pyramid. The first smooth-sided one was built by Pharaoh Sneferu, who ruled between c.2613 and 2589 B.C.

The most imposing example of a funerary tomb is the Great Pyramid of Giza, made for Sneferu's son: Khufu (c.2589–2566 B.C.), being the last surviving wonder of the ancient world and the largest pyramid in Egypt. The stone blocks used for pyramids were held together by mortar, and the entire structure was covered with highly polished white limestone, with their tops topped in gold. What we see today is actually the core structure of the pyramid. Inside, narrow passages led to the royal burial chambers. Despite being highly associated with Ancient Egypt, pyramids have been built by other civilisations to, like the Mayans.

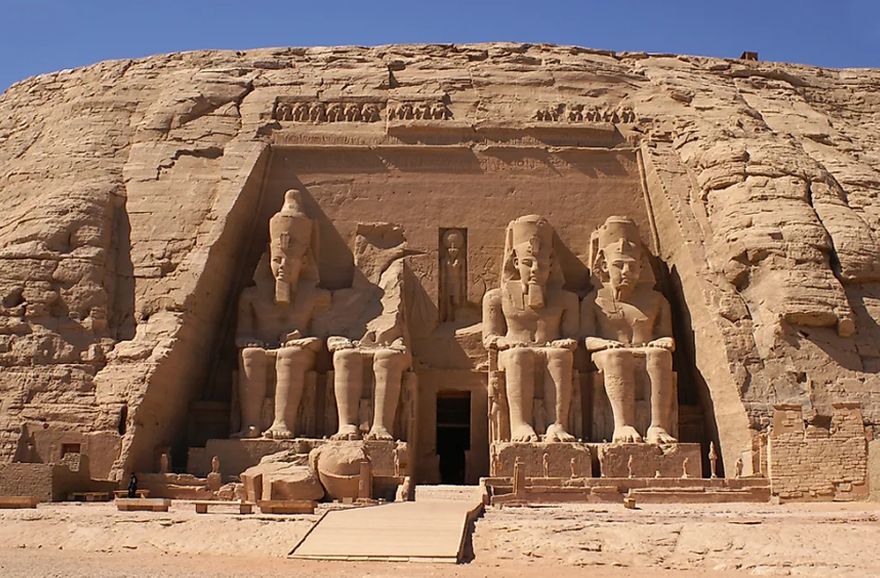

Due to the lack of resources and a shift in power towards priesthood, ancient Egyptians stepped away from pyramids, and temples became the focal point of cult construction. Just like the pyramids, Ancient Egyptian temples were also spectacular and monumental. They evolved from small shrines made of perishable materials to large complexes, and by the New Kingdom (circa 1550–1070 B.C.) they have become massive stone structures consisting of halls and courtyards.

The temple represented a sort of 'cosmos' in stone, a copy of the original mound of creation on which the god could rejuvenate himself and the world. The entrance consisted of a twin gateway (pylon), symbolizing the hills of the horizon. Inside there were columned halls symbolizing a primeval papyrus thicket. It was followed by a series of hallways of decreasing size until the sanctuary was reached, where a god's cult statue was placed. Back in ancient times, temples were painted in bright colours, mainly red, blue, yellow, green, orange, and white. Because of the desert climate of Egypt, some parts of these painted surfaces were preserved well, especially in the interiors.

An architectural element specific to ancient Egyptian architecture is the cavetto cornice (a concave moulding), introduced by the end of the Old Kingdom. It was widely used to accentuate the top of almost every formal pharaonic building. Because of how often it was used, it will later decorate many Egyptian Revival buildings and objects.

The Great Sphinx of Giza dating from around 2500 B.C. Giza, Egypt, recent studies suggest the Sphinx was built at 7000 B.C.

Temple Complex and Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, Egypt, 2667–2648 B.C., by Architect Imhotep

Hypostyle Hall of the Great Temple at Karnak, Luxor, Egypt, c.1294–1213 B.C.

The relocated Great Temple of Abu Simbel (Egypt), c.1264 B.C.

Island of Philae - relocated Temple of Isis built beginning ca. 280 B.C. Aswan, Egypt

GREECE

Ancient Greek architecture

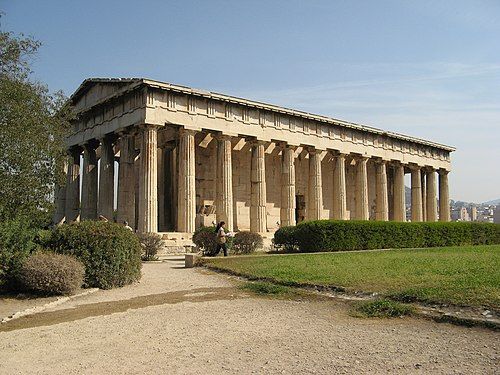

Unlike how most of us see them today, all Egyptian, Greek, and Roman sculptures and temples were initially painted in bright colours. They became white because of hundreds of years of neglect and vandalism provoked by Christians during the Early Middle Ages, who saw them as 'pagan' and believed that they promoted idolatry. Without a doubt, ancient Greek architecture, together with Roman, is one of the most influential styles of all time.

Since the advent of the Classical Age in Athens, in the 5th century BC, the Classical way of building has been deeply woven into a Western understanding of architecture and, indeed, of civilization itself. From circa 850 BC to circa 300 A.D., ancient Greek culture flourished on the Greek mainland, on the Peloponnese, and on the Aegean islands. Five of the Wonders of the World were Greek: the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, the Colossus of Rhodes, and the Lighthouse of Alexandria. However, Ancient Greek architecture is best known for its temples, many of which are found throughout the region, and the Parthenon is a prime example of this. Later, they will serve as inspiration for Neoclassical architects during the late 18th and 19th centuries.

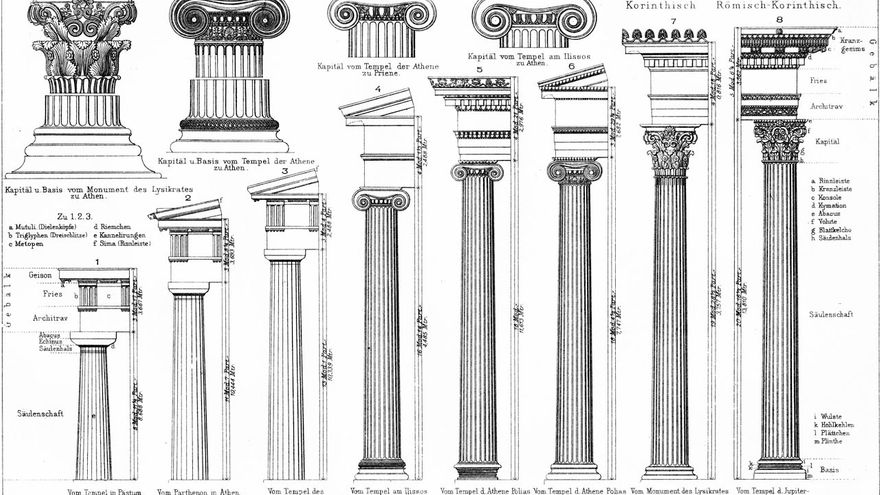

The most well-known temples are the Parthenon and the Erechtheion, both on the Acropolis of Athens. Another type of important Ancient Greek building was the theatre. Both temples and theatres used a complex mix of optical illusions and balanced ratios. Ancient Greek temples usually consist of a base with continuous stairs of a few steps at each edge (known as crepidoma), a cella (or naos) with a cult statue in it, columns, an entablature, and two pediments, one on the front side and another in the back. By the 4th century B.C., Greek architects and stonemasons had developed a system of rules for all buildings known as the orders: the Doric, the Ionic, and the Corinthian.

They are most easily recognised by their columns (especially by the capitals). The Doric column is stout and basic, the Ionic one is slimmer and has four scrolls (called volutes) at the corners of the capital, and the Corinthian column is just like the Ionic one, but the capital is completely different, being decorated with acanthus leaves and four scrolls. Besides columns, the frieze was different based on the order. While the Doric one has metopes and triglyphs with guttae, Ionic and Corinthian friezes consist of one big continuous band with reliefs. Besides the columns, the temples were highly decorated with sculptures, in the pediments, friezes, metopes, and triglyphs.

Ornaments used by Ancient Greek architects and artists include palmettes, vegetal or wave-like scrolls, lion mascarons (mostly on lateral cornices), dentils, acanthus leaves, bucrania, festoons, egg-and-dart, rais-de-cœur, beads, meanders, and acroteria at the corners of the pediments. Pretty often, ancient Greek ornaments are used continuously, as bands. They will later be used in Etruscan, Roman, and post-medieval styles that tried to revive Greco-Roman art and architecture, like Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassical, etc. Looking at the archaeological remains of ancient and medieval buildings it is easy to perceive them as limestone and concrete in a grey taupe tone and make the assumption that ancient buildings were monochromatic.

However, architecture was polychromed in much of the Ancient and Medieval world. One of the most iconic Ancient buildings, the Parthenon (c. 447–432 BC) in Athens, had details painted with vibrant reds, blues, and greens. Besides ancient temples, Medieval cathedrals were never completely white. Most had coloured highlights on capitals and columns. This practice of colouring buildings and artworks was abandoned during the early Renaissance.

This is because Leonardo da Vinci and other Renaissance artists, including Michelangelo, promoted a colour palette inspired by the ancient Greco-Roman ruins, which because of neglect and constant decay during the Middle Ages, became white despite being initially colourful. The pigments used in the ancient world were delicate and especially susceptible to weathering. Without necessary care, the colours exposed to rain, snow, dirt, and other factors, vanished over time, and this way Ancient buildings and artworks became white like they are today and were during the Renaissance.

Temple of Hera I at Paestum, Italy 550 B.C. unknown architect

Temple of Hephaestus on the Agoraios Kolonos Hill (Athens, Greece), c.449 BC, architect Ictinus

Erechtheion on the Acropolis in Athens, with its Ionic columns and caryatid porch, 421–405 BC Architect Mnesikles

Tholos of the Sanctuary of Athena Pronaia (Delphi, Greece), 380–360 BC, by Theodoros of Phocaea

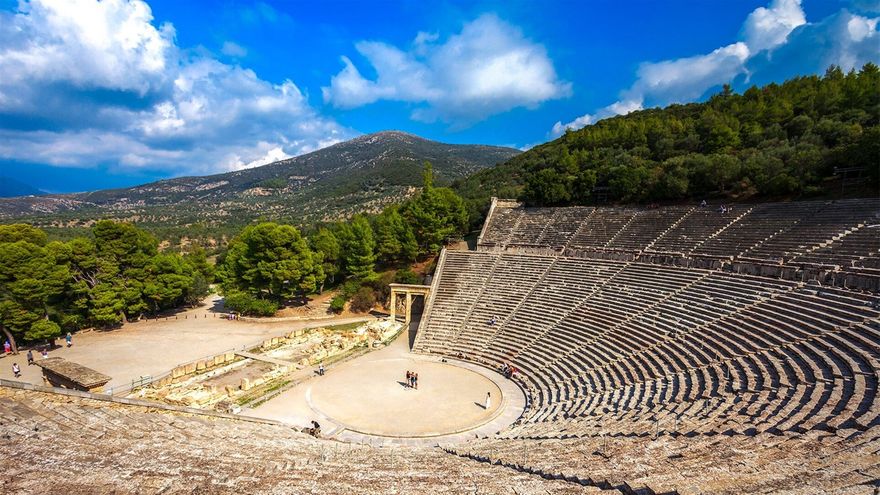

Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus (Epidaurus, Greece), 3rd century B.C. Architect Polykleitos

Temple of Olympian Zeus or Olympieion construction began in 174 B.C. and completed in 131 A.D.

Illustration of Doric, Ionic. and Corinthian columns and entablatures

ROMAN ERA

Ancient Roman architecture

The architecture of ancient Rome has been one of the most influential in the world. Its legacy is evident throughout the medieval and early modern periods, and Roman buildings continue to be reused in the modern era in both New Classical and Postmodern architecture. It was particularly influenced by Greek and Etruscan styles. A range of temple types was developed during the republican years (509–27 BC), modified from Greek and Etruscan prototypes.

Wherever the Roman army conquered, they established towns and cities, spreading their empire and advancing their architectural and engineering achievements. While the most important works are to be found in Italy, Roman builders also found creative outlets in the western and eastern provinces, of which the best examples preserved are in modern-day North Africa, Turkey, Syria, and Jordan. Extravagant projects appeared, like the Arch of Septimius Severus in Leptis Magna (present-day Libya, constructed in 216 A.D.), with broken pediments on all sides, or the Arch of Caracalla in Tebessa (Thebeste in present-day Algeria, constructed in c. 214 A.D.), with paired columns on all sides, projecting entablatures and medallions with divine busts.

Due to the fact that the empire was formed from multiple nations and cultures, some buildings were the product of combining the Roman style with the local tradition. An example is the Palmyra Arch (present-day Syria, constructed in c.212–220), some of its arches being embellished with a repeated band design consisting of four ovals within a circle around a rosette, which are of Eastern origin. Surpassing most civilisations of their time, the Romans developed new engineering skills, architectural techniques, and materials. Among the many Roman architectural achievements were domes, which were created for temples, baths, villas, palaces, and tombs.

The most well-known example is the one of the Pantheon in Rome, being the largest surviving Roman dome and having a large oculus at its centre. Another important innovation is the rounded stone arch, used in arcades, aqueducts, and other structures.

Besides the Greek orders (Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian), the Romans invented two more. The Tuscan order was influenced by the Doric, but with un-fluted columns and a simpler entablature with no triglyphs or guttae, while the Composite was a mixed order, combining the volutes of the Ionic order capital with the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian order. Between 30 and 15 B.C., the architect and engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio published a major treatise, De Architectura, which influenced architects around the world for centuries. As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissance as the first book on architectural theory, as well as a major source in the canon of classical architecture.

Just like the Greeks, the Romans built amphitheatres. The largest amphitheatre ever built, the Colosseum in Rome could hold around 50,000 spectators. The oldest stone amphitheatre was the one built in 70 B.C. in Pompeii.

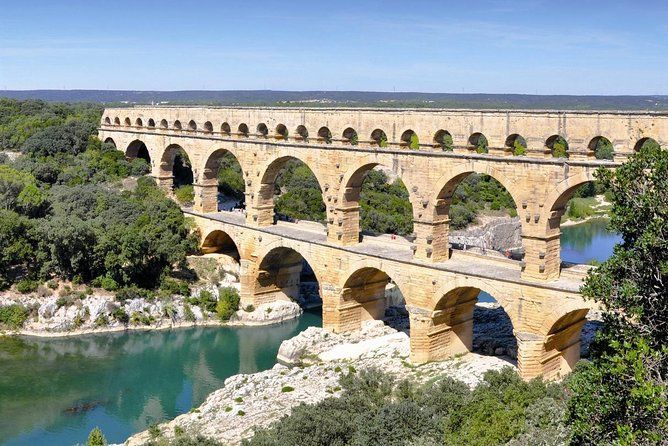

Another iconic Roman structure that demonstrates their precision and technological advancement is the Pont du Gard in southern France, the highest surviving Roman aqueduct. One of the most important innovations of the Romans was widespread provision of running water. The Roman aqueduct was a channel used to transport fresh water to highly populated areas. Though earlier civilizations in Egypt and India also built aqueducts, the Romans improved on the structure and built an extensive and complex network across their territories.

Evidence of aqueducts remain in parts of modern-day France, Spain, Greece, North Africa, and Turkey. Aqueducts required a great deal of planning. They were made from a series of pipes, tunnels, canals, and bridges. Gravity and the natural slope of the land allowed aqueducts to channel water from a freshwater source, such as a lake or spring, to a city. As water flowed into the cities, it was used for drinking, irrigation, and to supply hundreds of public fountains and baths.

Roman aqueduct systems were built over a period of about 500 years, from 312 B.C. to A.D. 226. Both public and private funds paid for construction. High-ranking rulers often had them built; the Roman emperors Augustus, Caligula, and Trajan all ordered aqueducts built. The most recognizable feature of Roman aqueducts may be the bridges constructed using rounded stone arches. Some of these can still be seen today traversing European valleys.

However, these bridged structures made up only a small portion of the hundreds of kilometers of aqueducts throughout the empire. The capital in Rome alone had around 11 aqueduct systems supplying freshwater from sources as far as 92 km away (57 miles). Despite their age, some aqueducts still function and provide modern-day Rome with water. The Aqua Virgo, an aqueduct constructed by Agrippa in 19 B.C. during Augustus’ reign, still supplies water to Rome’s famous Trevi Fountain in the heart of the city.

The Colosseum in Rome, begun under Vespasian 72 A.D. and completed in 80 AD under Titus

Pont du Gard at Vers-Pont-du-Gard, Gard, France, a Roman aqueduct, 40–60 A.D.

Maison Carrée, a Roman Temple at Nîmes, France, built during 4–7 A.D.

Roman Triumphal Arch at Timgad, Batna, Algeria, Completion date c. 100 A.D.

Library of Celsus at Ephesus, Turkey, built from 112–117 A.D.

The Pantheon in Rome, built by the Emperor Hadrian on the site of an earlier building commissioned by Marcus Agrippa, dedicated c. 126 AD.

The Theatre at Aspendos, Turkey, built during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161-180 AD), architect Zeno the Greek

Arch of Constantine at Rome, commissioned to commemorate Constantine's victory over Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge in 312 A.D.

EARLY CHRISTIAN EUROPE

Early Christian Architecture

Christian architecture started to develope after 313 A.D and Constantine's conversion to Christianity. The rapidly growing Christian population, now supported by the state, needed to build larger and grander public buildings for worship than the mostly discreet meeting places they had been using, which were typically in or among domestic buildings. Pagan temples remained in use for their original purposes for some time and, at least in Rome, even when deserted were shunned by Christians until the 6th or 7th centuries, when some were converted to churches.

Elsewhere this happened sooner. Architectural formulas for temples were unsuitable, not simply for their pagan associations, but because pagan cult and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open sky in the sight of the gods, with the temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, as a windowless backdrop.

The usable model at hand, when Emperor Constantine I wanted to memorialize his imperial piety, was the familiar conventional architecture of the basilica. There were several variations of the basic plan of the secular basilica, always some kind of rectangular hall, but the one usually followed for churches had a center nave with one aisle at each side, and an apse at one end opposite to the main door at the other. In, and often also in front of, the apse was a raised platform, where the altar was placed and the clergy officiated. In secular buildings this plan was more typically used for the smaller audience halls of the emperors, governors, and the very rich than for the great public basilicas functioning as law courts and other public purposes.

This was the normal pattern used for Roman churches, and generally in the Western Empire, but the Eastern Empire, and Roman Africa, were more adventurous, and their models were sometimes copied in the West, for example in Milan. All variations allowed natural light from windows high in the walls, a departure from the windowless sanctuaries of the temples of most previous religions, and this has remained a consistent feature of Christian church architecture. Formulas giving churches with a large central area were to become preferred in Byzantine architecture, which developed styles of basilica with a dome early on.

A particular and short-lived type of building, using the same basilican form, was the funerary hall, which was not a normal church, though the surviving examples long ago became regular churches, and they always offered funeral and memorial services, but a building erected in the Constantinian period as an indoor cemetery on a site connected with early Christian martyrs, such as a catacomb.

The six examples built by Constantine outside the walls of Rome are: Old Saint Peter's Basilica, the older basilica dedicated to Saint Agnes of which Santa Costanza is now the only remaining element, San Sebastiano fuori le mura, San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, Santi Marcellino e Pietro al Laterano, and one in the modern park of Villa Gordiani. A martyrium was a building erected on a spot with particular significance, often over the burial of a martyr. No particular architectural form was associated with the type, and they were often small. Many became churches, or chapels in larger churches erected adjoining them.

With baptistries and mausolea, their often smaller size and different function made martyria suitable for architectural experimentation.

Among the key buildings, not all surviving in their original form are:

Constantinian Basilicas such as:

Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran, Rome

St Mary Major, Rome

Old Saint Peter's Basilica. Vatican

Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem

Church of the Nativity. Bethlehem

Saint Sofia Church, Sofia

Centralized Plan Santa Constanza, Rome, built as an Imperial mausoleum adjoining a funerary hall, part of the wall of which survives.

Church of St. George, Sofia

Surviving examples of medieval secular architecture mainly served for defense across various parts of Europe. Castles and fortified walls provide the most notable remaining non-religious examples of medieval architecture. New types of civic, military, as well as religious buildings begin to appear in Europe during this period.

Santa Sabina Interior, Rome built between 422 and 432 A.D.

Santa Costanza at Rome, Interior, 4th. Century A.D.

San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, Rome, Interior, 4th. Century A.D.

Pevensey Castle, England, built in the 4th. Century

BYZANTINE ERA

Byzantine architecture

Byzantine architects built city walls, palaces, hippodromes, bridges, aqueducts, and most importantly, churches. They left us many types of churches, including the basilica (the most widespread type, and the one that reached the greatest development). From basilica derive other two types, the circular one and the octagonal one. Another monumental type of church is the one in the shape of an Orthodox cross and with five domes. In Mainland Greece, the most widespread type of church was the cruciform one, with one or more domes. Also, a big number of churches of these shapes exist in Moscow, Novgorod, and Kyiv, as well as in Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia, and Albania.

Through modifications and adaptations of local inspiration, the Byzantine style will be used as the main source of inspiration for architectural styles in Eastern Orthodox countries. For example, in Romania, the Brâncovenesc style is highly based on Byzantine architecture, but also has individual Romanian characteristics. Just like how the Parthenon is the most famous monument of the Ancient Greek religion, Hagia Sophia remained an iconic church of Christianity. The temples of both religions differ substantially in terms of their exterior and interior aspect. In Antiquity, the exterior was the most important part of the temple, because, in the interior, where the cult statue of the deity to whom the temple was built was kept, only the priest had access. The ceremonies were held outside, and what the worshipers' viewed was the facade of the temple, consisting of columns, with an entablature and two pediments.

Meanwhile, Christian liturgies were held in the interior of the churches, the exterior usually having little to no ornamentation. Byzantine architecture often featured marble columns, coffered ceilings, and sumptuous decoration, including the extensive use of mosaics with golden backgrounds.

The building material used by Byzantine architects was no longer marble, which had been very much the rule for the Ancient Greeks. They used mostly stone and brick, and also thin alabaster sheets for windows. Mosaics were used to cover brick walls and any other surface where fresco wouldn't work. Good examples of mosaics from the proto-Byzantine era are in Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki (Greece), the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, and the Basilica of San Vitale, both in Ravenna (Italy), and Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Byzantine Architectural styles lasted a very great time, 1,500 years, and in fact, the elements are still visible in many modern churches built for Eastern Orthodox sects nowadays.

Interior of Hagia Sophia (Istanbul, Turkey), 537 A.D., by Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus

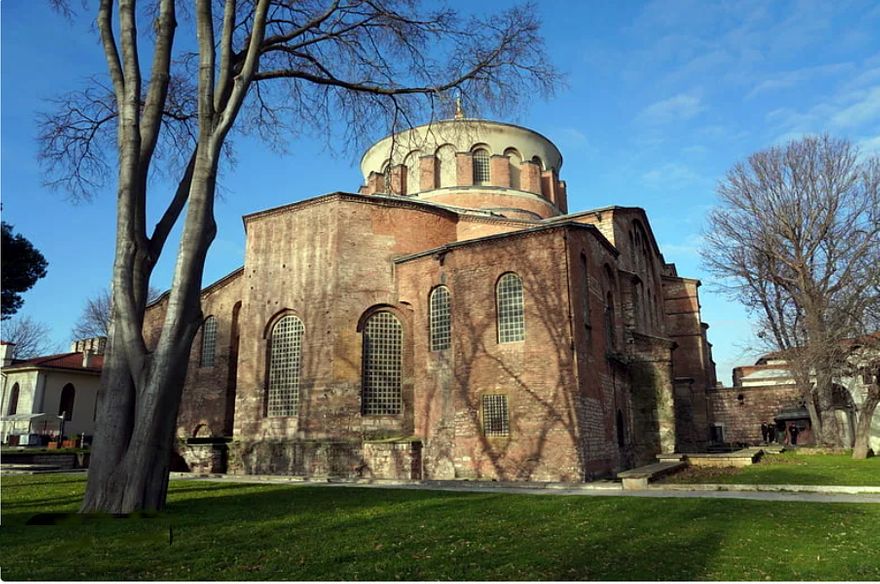

Exterior of Hagia Irene (Istanbul, Turkey), 6th century A.D.

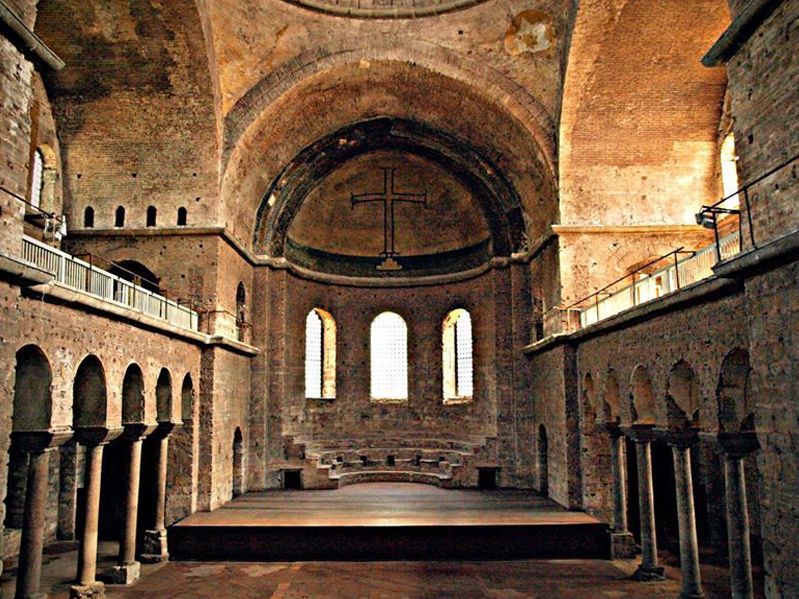

Interior of Hagia Irene (Istanbul, Turkey), 6th century A.D.

Basilica of San Vitale (Ravenna, Italy), 527-548 A.D.

Interior of Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe (Ravenna), 549 A.D.

Kapnikarea Church (Plaka, Athens), 1050 A.D.

ROMANESQUE ERA

Romanesque architecture

The term 'Romanesque' is rooted in the 19th century, when it was coined to describe medieval churches built from the 10th to 12th century, before the rise of steeply pointed arches, flying buttresses, and other Gothic elements. For 19th-century critics, the Romanesque reflected the architecture of stonemasons who evidently admired the heavy barrel vaults and intricately carved capitals of the ancient Romans, but whose own architecture was considered derivative and degenerate, lacking the sophistication of their classical models. Scholars in the 21st century are less inclined to understand the architecture of this period as a 'failure' to reproduce the achievements of the past and are far more likely to recognise its profusion of experimental forms, as a series of creative new inventions.

At the time, however, research questioned the value of Romanesque as a stylistic term. On the surface, it provides a convenient designation for buildings that share a common vocabulary of rounded arches and thick stone masonry, and appear in between the Carolingian revival of classical antiquity in the 9th century and the swift evolution of Gothic architecture after the second half of the 12th century. One problem, however, is that the term encompasses a broad array of regional variations, some with closer links to Rome than others. It should also be noted that the distinction between Romanesque architecture and its immediate predecessors and followers is not at all clear. There is little evidence that medieval viewers were concerned with the stylistic distinctions that we observe today, making the slow evolution of medieval architecture difficult to separate into neat chronological categories.

Nevertheless, Romanesque remains a useful word despite its limitations, because it reflects a period of intensive building activity that maintained some continuity with the classical past but freely reinterpreted ancient forms in a new distinctive manner. Romanesque cathedrals can be differentiated pretty easily from Gothic and Byzantine ones since they are characterized by the wide use of thick piers and columns, round arches, and severity.

Here, the possibilities of the round-arch arcade in both a structural and a spatial sense were once again exploited to the full. Unlike the sharply pointed arch of the later Gothic, the Romanesque round arch required the support of massive piers and columns. In comparison to Byzantine churches, Romanesque ones tend to lack complex ornamentation both on the exterior and interior. An example of this is the Saint-Front Cathedral at Périgueux, France, built in the early 12th century and designed on the model of St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, but lacking mosaics, leaving its interior very austere and minimalistic.

The Saint-Front Cathedral at Perigueux was rebuilt by architect Paul Abadie from 1852 to 1895. Only the bell tower and the crypts, both from the 12th century, were left from the previous structures.

Interior of Saint Michael of Hildesheim, Germany 1010-1031 A.D.

Abbey Church of Sainte-Foy (Conques, France), 1087-1107 A.D.

Interior of the Durham Cathedral (Durham, UK), 1093-1133 A.D.

Maria Laach Abbey (Glees, Germany), 1093-1230 A.D.

Interior of Périgueux Cathedral (Périgueux, France), early 12th century A.D. - 1896 A.D.

Cathedral Group at Pisa, Italy 1118 A.D.