Tesdorf Designs

Welcome to Architectural Information

WESTERN ARCHITECTURE 3

A HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE

NEOCLASSIC TO ART DECO PERIOD

NEOCLASSICISM CONTINUED.

Saline Royale d'Arc-et-Senans by Claude Nicolas Ledoux commissioned by Louis XV and built between 1775 and 1779 A.D..

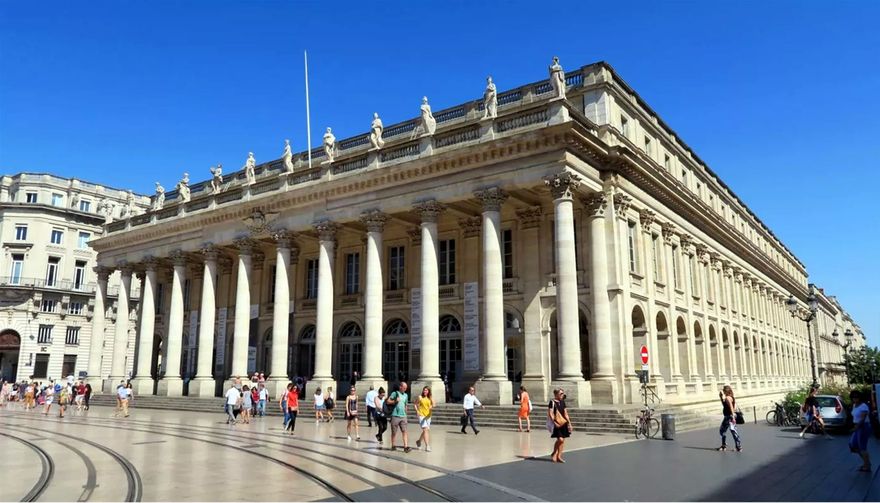

Grand Theater of Bordeaux (Bordeaux, France), 1777-1780 A.D., by Victor Louis

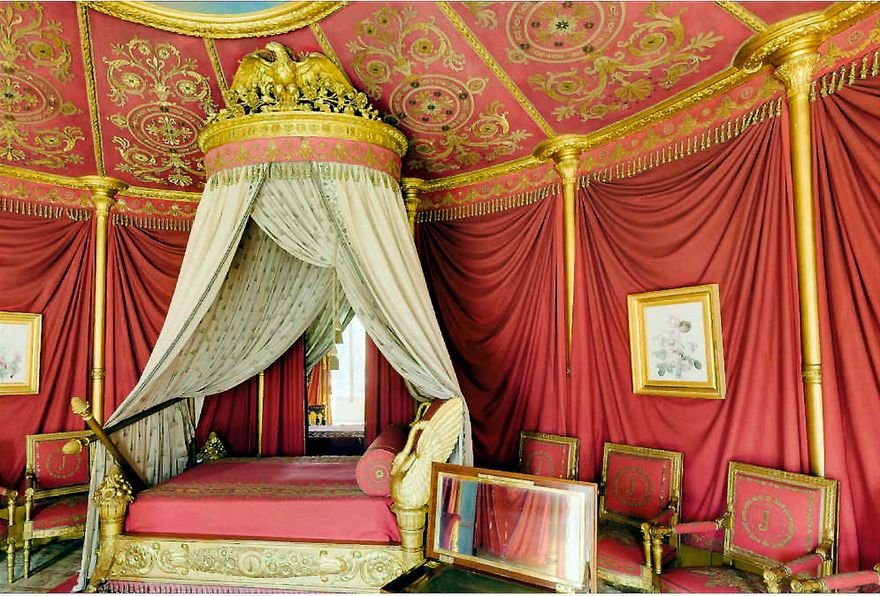

Empress Joséphine's Bedroom in Château de Malmaison (Rueil-Malmaison, France), 1800-1802 A.D., by Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine

Neue Wache (Berlin), 1816 A.D., by Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Salomo Sachs

Burns Monument (Edinburgh, Scotland) 1820-1831 A.D., by Thomas Hamilton

REVIVALISM & ECLECTICISM

Revivalism

The 19th century was dominated by a wide variety of stylistic revivals, variations, and interpretations. Revivalism in architecture is the use of visual styles that consciously echo the style of a previous architectural era. Modern-day Revival styles can be summarized within New Classical architecture, and sometimes under the umbrella term traditional architecture.

The idea that architecture might represent the glory of kingdoms can be traced to the dawn of civilisation, but the notion that architecture can bear the stamp of national character is a modern idea, that appeared in the 18th-century historical thinking and was given political currency in the wake of the French Revolution. As the map of Europe was repeatedly changing, architecture was used to grant the aura of a glorious past to even the most recent nations. In addition to the credo of universal Classicism, two new, and often contradictory, attitudes on historical styles existed in the early 19th century.

Pluralism promoted the simultaneous use of the expanded range of styles, while Revivalism held that a single historical model was appropriate for modern architecture. Associations between styles and building types appeared, for example Egyptian for prisons, Gothic for churches, or Renaissance Revival for banks and exchanges. These choices were the result of other associations: the pharaohs with death and eternity, the Middle Ages with Christianity, or the Medici family with the rise of banking and modern commerce. Whether their choice was Classical, medieval, or Renaissance, all revivalists shared the strategy of advocating a particular style based on national history, one of the great enterprises of historians in the early 19th century.

Only one historic period was claimed to be the only one capable of providing models grounded in national traditions, institutions, or values. Issues of style became matters of state. The most well-known Revivalist style is the Gothic Revival, which appeared in the mid-18th century in the houses of a number of wealthy antiquarians in England, a notable example being the Strawberry Hill House.

German Romantic writers and architects were the first to promote Gothic as a powerful expression of national character, and in turn, use it as a symbol of national identity in territories still divided. Johann Gottfried Herder posed the question 'Why should we always imitate foreigners as if we were Greeks or Romans?' In art and architecture history, the term Orientalism refers to the works of Western artists who specialised in Oriental subjects, produced from their travels in Western Asia, during the 19th century.

At that time, artists and scholars were described as Orientalists, especially in France. In India, during the British Raj, a new style, Indo-Saracenic, (also known as Indo-Gothic, Mughal-Gothic, Neo-Mughal, or Hindu style) was getting developed, which incorporated varying degrees of Indian elements into the Western European style. The Churches and convents of Goa are other examples of the blending of traditional Indian styles with western European architectural styles. Most Indo-Saracenic public buildings were constructed between 1858 and 1947, with the peaking at 1880 A.D.. The style has been described as "part of a 19th-century movement to project themselves as the natural successors of the Mughals". They were often built for modern functions such as transport stations, government offices, and law courts. It is much more evident in British power centres in the subcontinent like Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata, (Bombay, Madras and Calcutta.).

Eclecticism

Eclecticism is a 19th and early 20th-century architectural style in which a single piece of work incorporates a mixture of elements from previous historical styles to create something that is new and original. In architecture and interior design, these elements may include structural features, furniture, decorative motives, distinct historical ornament, and traditional cultural motifs or styles from other countries, with the mixture usually chosen based on its suitability to the project and overall aesthetic value.

The term is also used of the many architects of the 19th and early 20th centuries who designed buildings in a variety of styles according to the wishes of their clients, or their own. The styles were typically revivalist, and each building might be mostly or entirely consistent with the style selected, or itself an eclectic mixture. Gothic Revival architecture, especially in churches, was most likely to strive for a relatively "pure" revival style from a particular medieval period and region, while other revived styles such as Neoclassical, Baroque, Palazzo style, Jacobethan, Romanesque and many others were likely to be treated more freely.

Gothic Revival - Strawberry Hill House, Twickenham, London, by Horace Walpole, rebuilt the existing house in stages starting in 1749, 1760, 1772 & 1776 A.D.

Gothic Revival - Interior of the All Saints (London), 1850–1859 A.D., by William Butterfield

Eclectic - The Église Saint-Augustin de Paris, 1860–1868 A.D., by Victor Baltard

Gothic Revival - Saint Pancras Station, London, was designed by William Henry Barlow and opened on 1 October 1868 A.D.

Indo-Saracenic - The Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, previously Victoria Terminus (Mumbai, India), 1878–88 A.D., is a mixture of Romanesque, Gothic and Indian elements

BEAUX-ARTS

Beaux-Arts architecture

The Beaux-Arts style takes its name from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where it developed and where many of the main exponents of the style were studied. Due to the fact that international students studied here, there are buildings from the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century of this type all over the world, designed by architects like Charles Girault, Thomas Hastings, and Ion D. Berindey or Petre Antonescu.

The Beaux-Arts style evolved from the French classicism of the Style Louis XIV, and then French neoclassicism beginning with Style Louis XV and Style Louis XVI. French architectural styles before the French Revolution were governed by Académie royale d'architecture (1671–1793 A.D.), then, following the French Revolution, by the Architecture section of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

The Academy held the competition for the Grand Prix de Rome in architecture, which offered prize winners a chance to study the classical architecture of antiquity in Rome. The formal neoclassicism of the old regime was challenged by four teachers at the Academy, Joseph-Louis Duc, Félix Duban, Henri Labrouste, and Léon Vaudoyer, who had studied at the French Academy in Rome at the end of the 1820s. They wanted to break away from the strict formality of the old style by introducing new models of architecture from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Their goal was to create an authentic French style based on French models. Their work was aided beginning in 1837 A.D. by the creation of the Commission of Historic Monuments, headed by the writer and historian Prosper Mérimée, and by the great interest in the Middle Ages caused by the publication in 1831A.D. of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame by Victor Hugo. Their declared intention was to "imprint upon our architecture a truly national character." The style referred to as Beaux-Arts in English reached the apex of its development during the Second Empire (1852–1870 A.D. and the Third Republic that followed. The style of instruction that produced Beaux-Arts architecture continued without major interruption until 1968. The Beaux-Arts style heavily influenced the architecture of the United States in the period from 1880 A.D. to 1920. In contrast, many European architects of the period 1860–1914 outside France gravitated away from Beaux-Arts and toward their own national academic centers. Owing to the cultural politics of the late 19th century, British architects of Imperial classicism followed a somewhat more independent course, a development culminating in Sir Edwin Lutyens's New Delhi government buildings.

Today, from Bucharest to Buenos Aires and from San Francisco to Brussels, the Beaux-Arts style survives in opera houses, civic structures, university campuses commemorative monuments, luxury hotels, and townhouses. The style was heavily influenced by the (1860-1875 A.D.), designed by Charles Garnier, the masterpiece of the 19th-century renovation of Paris, dominating its entire neighbourhood and continuing to astonish visitors with its majestic staircase and reception halls. The Opéra was an aesthetic and societal turning point in French architecture. Here, Garnier showed what he called a style actually, which was influenced by the spirit of the time, aka Zeitgeist, and reflected the designer's personal taste.

Beaux-Arts façades were usually imbricated, or layered with overlapping classical elements or sculptures. Often façades consisted of a high rusticated basement level, after it a few floors high level, usually decorated with pilasters or columns, and at the top an attic level and/or the roof. Beaux-Arts architects were often commissioned to design monumental civic buildings symbolic of the self-confidence of the town or city. The style aimed for Baroque opulence through lavishly decorated monumental structures that evoked Louis XIV's Versailles. However, it wasn't just a revival of the Baroque, being more of a synthesis of Classicist styles, like Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassicism, and other styles.

Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, by architect Félix Duban, 1830-1861 A.D.

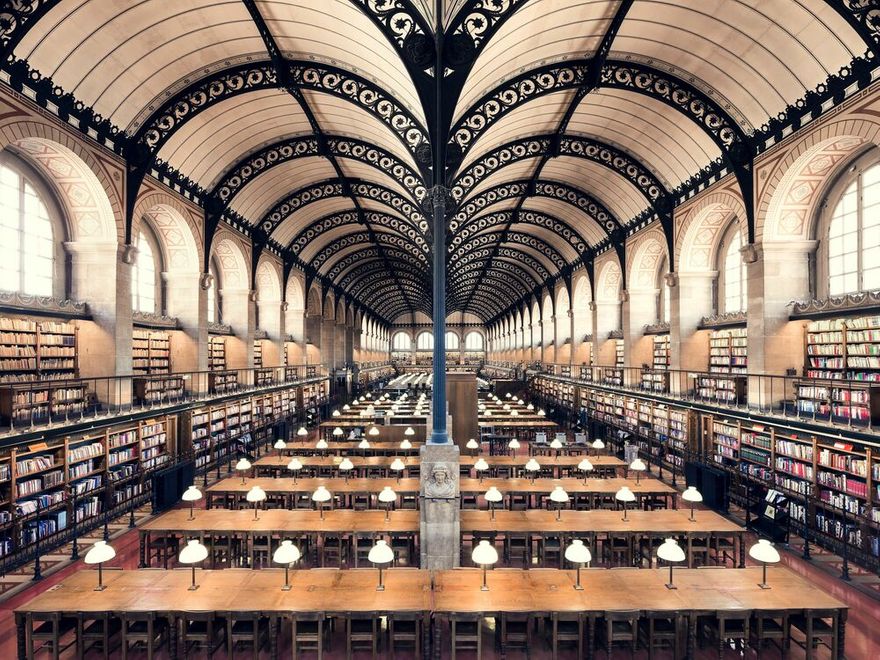

Bibliotheque Sainte-Genevieve at Paris, 1838-1851 A.D. by architect Henri Labrouste.

The Opera House at Paris, (1860-1875 A.D.), designed by Charles Garnier

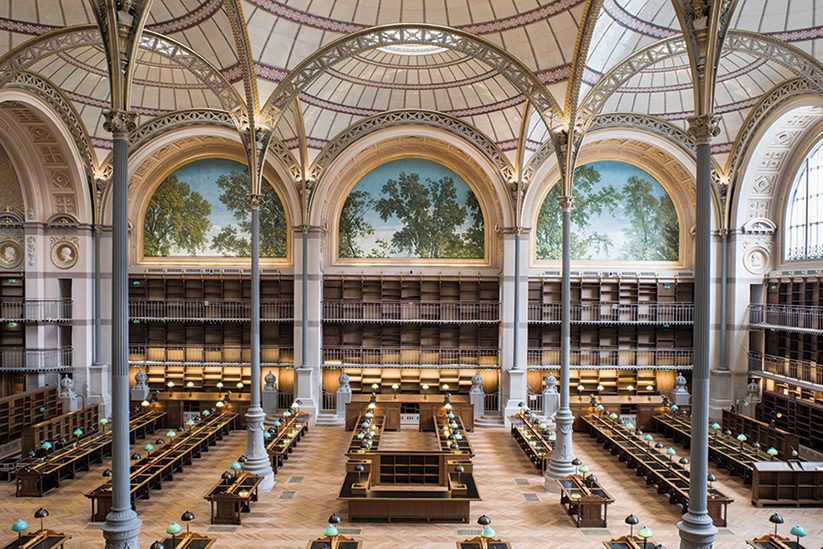

Bibliothèque Nationale Richelieu, Paris by Henri Labrouste, 1868 A.D.

Petit Palais (Paris), 1900, by Architect Charles Giraud

Rosecliff Mansion at Newport Rhode Island, USA, by Stanford White of McKim, Mead & White 1898-1902

Grand Central Terminal (New York City), 1903, by Reed, Stem, Warren, and Wetmore.

INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT & NEW TECHNOLOGIES

Industrial Architecture

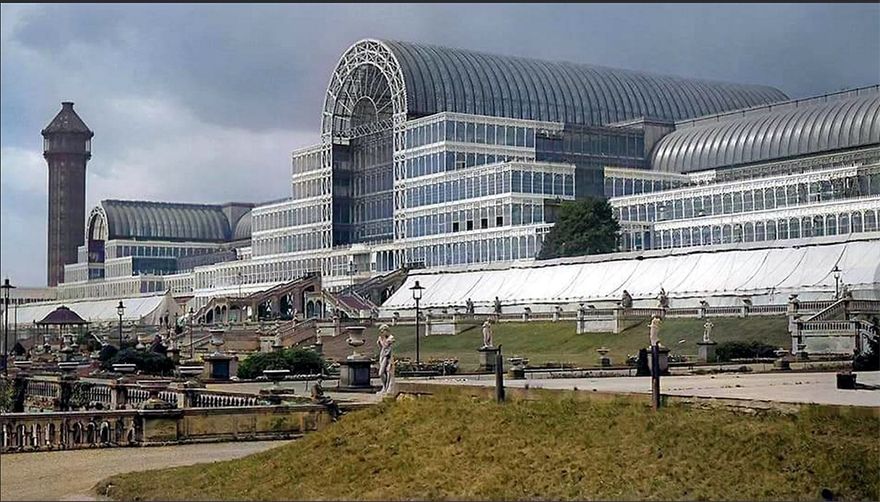

Because of the Industrial Revolution and the new technologies it brought, new types of buildings appeared. By 1850 A.D. iron was quite present in daily life at every scale, from mass-produced decorative architectural details and objects of apartment buildings and commercial buildings to train sheds. A well-known 19th-century glass & iron building is the Crystal Palace from Hyde Park (London), built to house the Great Exhibition, it had an appearance similar to a greenhouse. Its scale was daunting. The marketplace pioneered novel uses of iron and glass to create an architecture of display and consumption that made the temporary display of the world fairs a permanent feature of modern urban life.

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000 square feet (92,000 m2) exhibition space to display examples of technology developed in the Industrial Revolution. Designed by Joseph Paxton, the Great Exhibition building was 1,851 feet (564 m) long, with an interior height of 128 feet (39 m).

After the exhibition, the Palace was relocated to an area of South London known as Penge Place which had been excised from Penge Common. It was rebuilt at the top of Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, an affluent suburb of large villas. It stood there from June 1854 A.D. until its destruction by fire in November 1936.

Just after a year after the Crystal Palace was dismantled, Aristide Boucicaut opened what historians of mass consumption have labeled the first department store, Le Bon Marché in Paris. As the store expanded, its exterior took on the form of a public monument, being highly decorated with French Renaissance Revival motifs. The entrances advanced subtly onto the pavement, hoping to captivate the attention of potential customers. Between 1872 and 1874 A.D., the interior was remodeled by Louis-Charles Boileau, in collaboration with the young engineering firm of Gustave Eiffel. In place of the open courtyard required to permit more daylight into the interior, the new building focused on three skylight atria.

Antwerpen-Centraal railway station building was constructed between 1895 A.D. and 1905 as a replacement for the first station. The stone-clad building was designed by the architect Louis Delacenserie. The viaduct into the station is also a notable structure designed by local architect Jan Van Asperen.

Palm House, Kew Gardens, London, 1848 A.D., by Richard Turner and Decimus Burton

The Crystal Palace , London, built 1854 A.D,, by Joseph Paxton

La Grande Halle at La Villette, Paris, 1865–1867 A.D. Designed by Jules de Mérindol and Louis-Adolphe Janvier

Le Moulin Saulnier, now part of the Menier chocolate factory in Noisiel, France. Built in 1872 A.D.

Interior of Le Bon Marché (Paris), 1872 A.D., by Louis-Charles Boileau, with the engineering firm of Gustave Eiffel

Antwerpen-Centraal railway station, Antwerp, Belgium, 1895–1905 A.D., by Louis Delacenserie

ART NOUVEAU

Art Nouveau Architecture & Ornamentation

Popular in many countries from the early 1890s until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Art Nouveau was an influential although relatively brief art and design movement and philosophy. Despite being a short-lived fashion, it paved the way for the modern architecture of the 20th century. Between c. 1870 and 1900, a crisis of historicism occurred, during which the historicist culture was critiqued, one of the voices being Friedrich Nietzsche who in 1874 A.D, diagnosed 'a malignant historical fervour' as one of the crippling symptoms of a modern culture burdened by archaeological study and faith in the laws of historical progression.

Focusing on natural forms, asymmetry, sinuous lines, and whiplash curves, architects and designers aimed to escape the excessively ornamental styles and historical replications, popular during the 19th century. However, the style wasn't completely new, since Art Nouveau artists drew on a huge range of influences, particularly Beaux-Arts architecture, the Arts and Crafts movement, aestheticism, and Japanese art. Buildings used materials associated in the 19th century with modernity, such as cast iron and glass. A good example of this is the Paris Metro entrance at Porte Dauphine by Hector Guimard (1900). It's cast-iron and glass canopy is as much sculpture as it is architecture. In Paris, Art Nouveau was even called Le Style Métro by some. The interest in stylized organic forms of ornamentation originated in the mid-19th century when it was promoted in The Grammar of Ornament (1854 A.D.), a pattern book by British architect Owen Jones (architect) (1809-1874 A.D.).

Viennese architect Otto Wagner (1841-1918) was part of the "Viennese Secession" movement at the end of the 19th century, which was marked by a revolutionary spirit of enlightenment. The Secessionists revolted against the Neoclassical styles of the day, and, instead, adopted the anti-machine philosophies of William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. Wagner's architecture was a cross between traditional styles and Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil, as it was called in Austria. He is one of the architects credited with bringing modernity to Vienna, and his architecture remains iconic in Vienna, Austria.

Whiplash curves and sinuous organic lines are its most familiar hallmarks, however, the style can not be summarized only to them, since its forms are much more varied and complex. The movement displayed many national interpretations. Depending on where it manifested, it was inspired by Celtic art, Gothic Revival, Rococo Revival, and Baroque Revival. In Hungary, Romania, and Poland, for example, Art Nouveau incorporated folkloric elements. This is true especially in Romania because it facilitated the appearance of the Romanian Revival style, which draws inspiration from Brâncovenesc architecture and traditional peasant houses and objects.

The style also had different names, depending on countries. In Britain, it was known as Modern Style, in the Netherlands as Nieuwe Kunst, in Germany and Austria as Jugendstil, in Italy as Liberty style, in Romania as Arta 1900, and in Japan as Shiro-Uma. It would be wrong to credit any particular place as the only one where the movement appeared since it seems to have arisen in multiple locations.

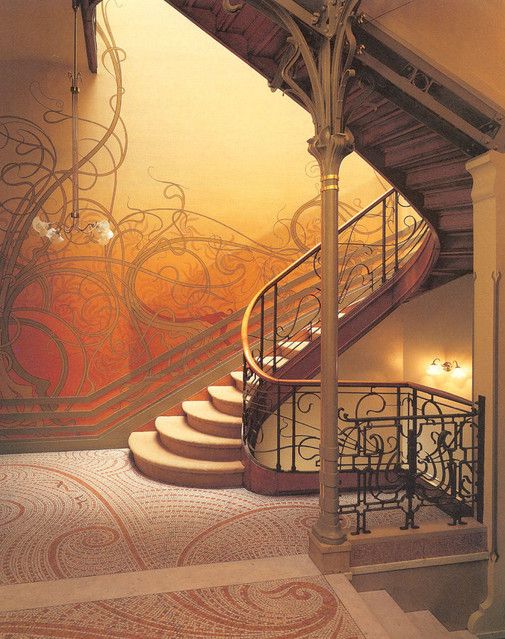

Staircase in Hôtel Tassel at Brussels, Belgium, 1894 A.D., by Victor Horta

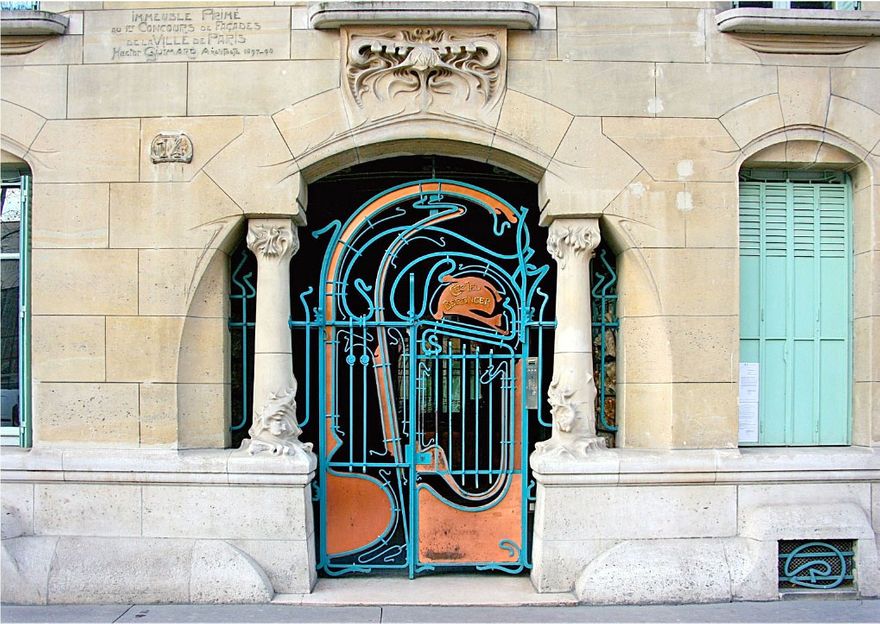

Doorway to the Castel Béranger in Paris, 1895–1898 A.D. by Hector Guimard

Secession Art Exhibition Building , Vienna, Austria, 1897 A.D. by Joseph Maria Olbrich

Majolika Haus, Vienna, Austria 1898-1899 A.D. Architect Otto Wagner

Interior of Bijouterie Fouquet (now in Musée Carnavalet, Paris), c. 1900, by Alphonse Mucha

The Porte Dauphine Métro Station Entry in Paris, by Hector Guimard, 1900

Interior of the Villa Majorelle, 1 rue Louis-Majorielle, Nancy, France, designed by architect Henri Sauvage 1901-1902.

Casa Batlló in Barcelona, Spain, 1904–1906, by Antoni GaudI

MODERN & INTER-WAR

Modern & Inter-War Architecture

Modern Architecture emerged at the end of the 19th century from revolutions in technology, engineering, and building materials, and from a desire to break away from historical architectural styles and to invent something that was purely functional and new. The origins of Modern lie in diverse historic, technical and sociological origins and pre-conditions. The revolution in materials came first, with the use of cast iron, drywall, plate glass, and reinforced concrete, to build structures that were stronger, lighter, and taller.

The cast plate glass process was invented in 1848 A.D., allowing the manufacture of very large windows. The Crystal Palace by Joseph Paxton at the Great Exhibition of 1851 A.D. was an early example of iron and plate glass construction, followed in 1864 A.D. by the first glass and metal curtain wall. These developments together led to the first steel-framed skyscraper, the ten-story Home Insurance Building in Chicago, built in 1884 A.D. by William Le Baron Jenney. The iron frame construction of the Eiffel Tower, then the tallest structure in the world, captured the imagination of millions of visitors to the 1889 A.D. Paris Universal Exposition.

French industrialist François Coignet was the first to use iron-reinforced concrete, that is, concrete strengthened with iron bars, as a technique for constructing buildings. In 1853 A.D. Francois Coignet built the first iron reinforced concrete structure, a four-storey house in the suburbs of Paris.

A further important step forward was the invention of the safety elevator by Elisha Otis, first demonstrated at the New York Crystal Palace exposition in 1854 A.D., which made tall office and apartment buildings practical. Another important technology for the new architecture was electric light, which greatly reduced the inherent danger of fires caused by gas in the 19th century. The debut of new materials and techniques inspired architects to break away from the neoclassical and eclectic models that dominated European and American architecture in the late 19th century, most notably eclecticism, Victorian and Edwardian architecture, and the Beaux-Arts architectural style.

This break with the past was particularly urged by the architectural theorist and historian Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. In his 1872 A.D. book Entretiens sur L'Architecture, he urged: "use the means and knowledge given to us by our times, without the intervening traditions which are no longer viable today, and in that way, we can inaugurate a new architecture. For each function its material; for each material its form and its ornament." This book influenced a generation of architects, including Louis Sullivan, Victor Horta, Hector Guimard, and Antoni Gaudí.

The definitive texts of Modern Architecture were written by le Corbusier :

Vers une architecture, The City of Tomorrow and Its Planning, When the Cathedrals were white, The Athens Charter, Une Petite Maison, Le voyage d'Orient, La Cite Radieuse, Le Corbusier, The Modulor & Modulor 2

Rejecting ornament and embracing minimalism and modern materials, Modernist architecture appeared across the world in the early 20th century. The First World War's devastation and the Increasing Industrialisation of Society spurred Modern Architecture on. It developed initially in Europe Post World War I, focusing on functionalism and the avoidance of decoration. Modernism reached its peak during the 1920s and 1930s with Le Corbusier, the Bauhaus, and the International Style, both characterised by asymmetry, flat roofs, large windows, metal, glass, white rendering, and open-plan interiors.

Villa Steiner, Vienna, Austria, 1910 designed by Adolf Loos

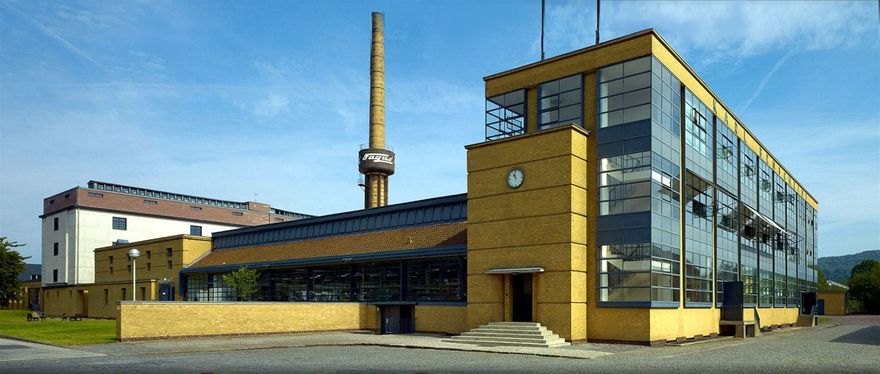

Fagus Factory at Alfeld-an-der-Leine, Germany, 1911, designed by Walter Gropius.

House for Tristan Tzara in Paris, France, 1925-1926, designed by Adolf Loos.

Zonnestraal Sanatorium at Hilversum, the Netherlands, 1925-1927, by Jan Duiker and Bernard Bijvoet

Weissenhof Settlement Flats at Stuttgart, Germany 1927, by Le Corbusier, other buildings by Mies van der Rohe and other architects.

Villa Savoie at Poissy, France, 1929 by Le Corbusier

Paimio Sanatorium, a former tuberculosis sanatorium in Paimio, Finland, designed by Alvar Aalto. The commission came from a competition held in held in 1929.

Villa Tugendhat at Brno, the Czech Republic, 1930, by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich

ART DECO

Art Deco and Streamline Moderne

Art Deco, short for Arts Décoratifs, was named retrospectively after an exhibition held in Paris in 1925, originated in France as a luxurious, highly decorated style. It then spread quickly throughout the world - most dramatically in the United States - becoming more streamlined and modernistic through the 1930s. The style was pervasive and popular, finding its way into the design of everything from jewellery to film sets, from the interiors of ordinary homes to cinemas, luxury streamliners and hotels. Its exuberance and fantasy captured the spirit of the 'roaring 20s' and provided an escape from the realities of the Great Depression during the 1930s.

Art Deco influenced the design of buildings, furniture, jewellery, fashion, cars, cinemas, trains, ocean liners, and everyday objects such as radios and vacuum cleaners. Art Deco combined modern styles with fine craftsmanship and rich materials. During its heyday, it represented luxury, glamour, exuberance, and faith in social and technological progress. From its outset, Art Deco was influenced by the bold geometric forms of Cubism and the Vienna Secession; the bright colours of Fauvism and of the Ballets Russes; the updated craftsmanship of the furniture of the eras of Louis Philippe I and Louis XVI; and the exoticised styles of China, Japan, India, Persia, ancient Egypt and Maya art. It featured rare and expensive materials, such as ebony and ivory, and exquisite craftsmanship.

The Empire State Building, Chrysler Building, and other skyscrapers of New York City built during the 1920s and 1930s are monuments to the style. In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, Art Deco became more subdued. New materials arrived, including chrome plating, stainless steel and plastic. A sleeker form of the style, called Streamline Moderne, appeared in the 1930s, featuring curving forms and smooth, polished surfaces.

Art Deco is one of the first truly international styles, but its dominance ended with the beginning of World War II and the rise of the strictly functional and unadorned styles of modern architecture and the International Style of architecture that followed. Bold colours were often applied on low-reliefs. Predominant materials include chrome plating, brass, polished steel and aluminium, inlaid wood, stone and stained glass.

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (Paris), 1911–1913, by Auguste Perret

The boudoir of fashion designer Jeanne Lanvin (now in the Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris), before 1925, by Armand-Albert Rateau

La Samaritaine department store in Paris, France, by Henri Sauvage (1925–28)

Chrysler Building (New York City), 1930, by William Van Allen

Lincoln Theater in Miami Beach, Florida, by Thomas W. Lamb (1936)

Stairway of the Economic and Social Council in Paris, originally the Museum of Public Works, was built for the 1937 Paris International Exposition, by Auguste Perret (1937)

The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (Paris), 1911–1913, by Auguste Perret

Apartment of fashion designer Jeanne Lanvin (now in the Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris), before 1925, by Armand-Albert Rateau

La Samaritaine department store in Paris, France, by Henri Sauvage (1925–28)

The top of the Chrysler Building (New York City), 1930, by William Van Allen